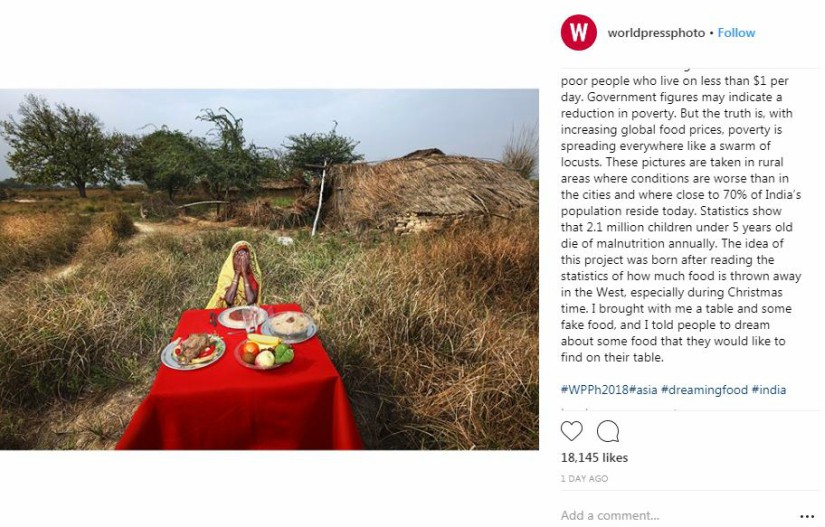

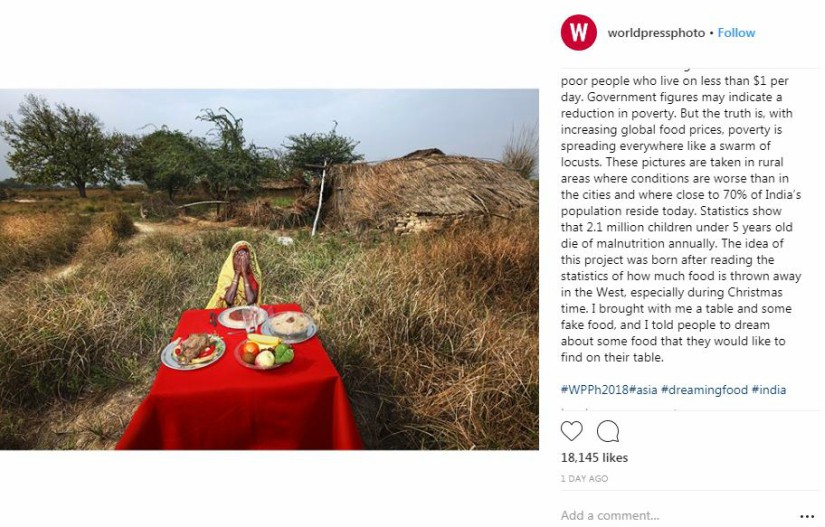

A conceptual photo project called Dreaming Food on impoverished Indians in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh is being criticised both by Indians and the international photo community as “poverty porn.”

The images, captured by Sicily-based independent photographer Alessio Mamo, show visibly undernourished children and adults in front of a table full of artificial food. The people in each photograph are hiding their eyes with their hands.

When Mamo shared the project on the World Press Photo’s Instagram feed on 22 July, the project got attention, but not in the way Mamo had intended. Over 1,300 people commented on the project, many of whom criticised it as “exploitative” and “insensitive.”

The Wrld Press Photo Foundation is an Amsterdam-based premier international nonprofit organisation that has led the international photojournalistic narrative for six decades. They have over 9,00,000 followers from around the world on Instagram.

On the World Press Photo Instagram feed, Mamo wrote that he embarked on the project after reading the statistics of how much food is wasted in the West, especially around Christmas.

“I brought with me a table and some fake food, and I told people to dream about some food that they would like to find on their table,” Mamo wrote in the Instagram post.

After the backlash on social media, where Instagram users called his work “cruel” and “inhuman”, Mamo posted a statement on Medium in response.

“The only goal of the concept was to let western people think, in a provocative way, about the waste of food,” he wrote.

Mamo’s argument that this project will make westerners less likely to waste food, and therefore somehow impact food scarcity abroad, is illogical. A person wasting food in Europe or the United States has no impact on food scarcity in another part of the world. Studies show that droughts, industrial farming, patenting of seeds, food distribution, pricing, and politics drive food scarcity and malnutrition.

Mamo is not the first Western photographer to have parachuted in the developing world to document poverty and malnutrition, especially for its shock value, or as Mamo wrote, because it is “provocative.” Many western photographers have documented the issue in the developing world for decades by exploiting poor people as props.

While most viewers are criticising the photographer, some media professionals are condemning World Press Photo. Since 2013, the organisation has been in the limelight for awarding images that the photojournalism community deemed ethically problematic, but only in relation to photo manipulation and staging. This is the first time images are being called into question due to issues related to the dignity and representation of the people in the photographs. Western institutions are rarely critical of images that propagate stereotypes.

Western photographers routinely travel to India to create images for Western consumption. They often come in with little research and cultural understanding of the place. They mostly rely on translators to help with both the story research and the interpretation, missing all nuance and complexity. Others push their already formed viewpoint onto the people or communities they are photographing.

Many photographers are primarily focused on making graphic and colorful images. They tend to focus their lenses on poor people, filthy streets, holy men, widows of Varanasi and cows. Western media outlets, journalism grants, and contests frequently support and reward such footage.

This continues to contribute to the West viewing India as a land of poverty, spiritual mecca and chaos. The images captured by most Western photographers are far from the actual representation of India and often feed into an unending cycle of “poverty porn”.

“Too many have come and done this kind of shameful work in India and their rewards just open the door for many others to think it’s OK. It isn’t. It’s just inexcusable,” Hari Adivarekar says in response to Mamo’s images. A Bangalore-based photojournalist, he is amongst the few Indian photographers who often use social media as means to question media outlets and photographers about problematic images.

By and large, the Indian photo community, media outlets and the public continue to remain silent on such issues. Galleries, photo festivals and media articles sometimes provide platforms for work that exoticises or portrays India in a negative light. This further validates not just the photographer but also a problematic visual language.

Not only that, India is an easy target for Western photographers because there are fewer barriers to gaining access necessary to photograph people. Unlike people in the West, Indians are less aware of issues surrounding privacy and informed consent. Just like Mamo, numerous Western photographers take advantage of this lack of understanding to create exotic or sensational work.

After the controversy broke, Mamo tried deflecting the criticism by claiming that the people he photographed willingly participated in the project. A nonprofit connected Mamo to his portrait sitters, which could create pressure for them to agree to be photographed due to fear of losing the resources from the NGO, Baltimore-based humanitarian photographer and filmmaker Elizabeth Pohl said.

This places the responsibility of the issue not only from the shoulders of the photographer onto that of the supporting NGO as well. NGOs helping Western photographers who parachute into the developing world to produce visual coverage could be ethically problematic at times, Pohl said.

“When a photographer enters a poor community anywhere in the world, there’s an inherent power balance,” Pohl said. She questioned if Mamo had received an informed consent and if he thought about other approaches to document food waste in the West such as photographing the story in the west.

Local photographers are more likely to have an intimate understanding not only about an issue faced by a community but also the cultural and historical context of the issue. A lack of understanding of the cultural and historical nuances of an issue often results in stereotyping people, place or culture.

Pohl believes that in some situations NGO’s and photo editors from Western media outlets flinch from hiring local photographers due to their limited English writing and reporting skills. Gatekeepers in the media world and NGOs give little importance to visual language as opposed to other skills. She emphasises that they should invest in training local photographers to do the jobs instead of looking westward.

“I have no problem with Western photographer photographing in a developing country as long they do not breach the dignity of the people being photographed,” Baramulla-based documentary photographer Showkat Nanda says. Nanda believes that Mamo’s series oversimplifies a complex issue.

“When photographers only document the negative aspects of people or a community, they propagate stereotypes, making the images colonial in nature,” Nanda said.

Adivarekar believes issues in visual representation are not necessarily an outcome of gender, race or nationality. He sees “parachuting” more as “a mindset and way of working”. In some cases it could be the classic example of a white male photographer photographing in India or any place that was once colonised or it could also be an urban Indian photographer parachuting into a rural area or a small town and making the same errors of judgment, he explains. Both the situation creates the same issues that of privilege, agency and consent, he asserts.

“Photography is by nature a colonial practice whereby power was given to the one owning the camera, hence the one telling the story,” says Laura Beltran Villamizar. She’s the projects picture editor at the NPR headquarters in Washington DC, and previously worked as an editor and communicator at World Press Photo.

Photographers and viewers need to be aware of the colonial nature of photography and how it is often used as a tool to reinforce dominant narratives that are “often sensationalised and racist representations of others,” Villamizar says. She points out that the current visual discourse is problematic because Western writers, photographers, editors and other media-makers overwhelmingly appropriate underrepresented cultures around the world for Western media consumption.

However, the viewers and photo community hold the power to change the existing visual narrative on the developing world. People in the developing world need to assert their agency by voicing their concerns about problematic images and privacy issues. Not only that, photographers should take the responsibility of photographing the “other” in a sensitive and dignified way, seriously. As photographer Pohl eloquently puts it, “It’s simple: just photograph others the way you would photograph your own family.”