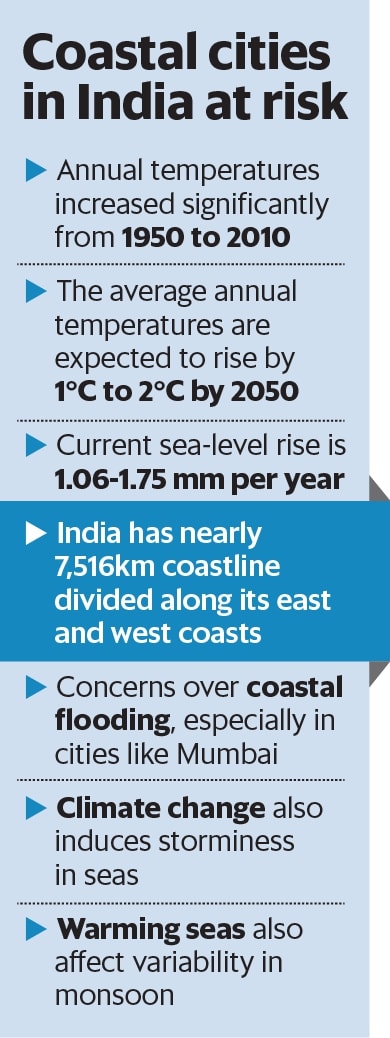

The sea level along India’s long coastline of nearly 7,516km is rising at an average 1.6-1.7 mm a year, show studies

New Delhi:

Average sea levels may rise by up to 30 feet around the world if humans continue to burn fossil and fuels causing temperatures to breach the threshold of 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels in the next few thousand years, says new research.

The Paris Agreement requires countries to limit their carbon emissions to keep the overall warming of Earth to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

With over a billion people living in coastal zones around the world, the impact of rising sea levels on human population along the coast could be larger than expected, especially in poor and developing countries, where millions are directly or indirectly depended on the oceans for their livelihood.

Demonstrating the co-relation between the cumulative carbon emissions and future sea-levels over time, the new study published in Nature Climate Change also raises concerns over the impending economic losses in the world’s largest coastal cities due to coastal flooding.

“The sea level rise we have seen thus far is just the tip of a very large iceberg. The big question is whether we can stabilize the system and find new energy sources. If not, we are on the way to a slow-motion catastrophe,” said co-author of the study Alan Mix from Oregon State University.

Researchers highlight that at present, over 10 billion tonnes of carbon is being emitted globally, which would mean that the 2-degree threshold would probably be reached within next 60 years.

According to oceanographers, among South-Asian countries, Bangladesh is most-vulnerable, but India with its vast coastline of nearly 7,516 km on the east and west also needs to be proactive, considering the vast numbers of people who are dependent on the oceans for their livelihood.

According to studies conducted, the sea-level is rising at an average rate of 1.6-1.7 mm per year along the Indian coast, but it is not uniform.

“It varies from 5mm in Sunderbans to less than a 1 mm per year in some of the areas in the west coast. Sunderbans are most vulnerable, not only because its low-lying, but also because the land is also sinking,” said S C Shenoi, director, Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services, Hyderabad.

Scientists and researchers have prepared a vulnerability index of the entire coast of India, which not only covers threats due to sea level rise but also Tsunamis.

“Rising sea levels have not really alarmed people yet because their response time is much longer than temperature. Smart countries will use that to their advantage and begin adaptation strategies over time,” said Peter Clark, lead author from Oregon State University, emphasizing the need to consider the rise in sea levels as important factor while making future policy decisions on limiting carbon emissions.

“The sea levels are the highest ever globally. Though it is expected to rise by less than a metre by the end of this century, but even that is crucial, especially for India where places like Mumbai, could face consequences as happened in 2005,” said S W A Naqvi, former director, National Institute of Oceanography (NIO), Goa.

However, Naqvi highlights that the climate change will not just lead to rise in sea-levels, but is set to affect storminess in the seas, which is a significant concern. “Most importantly, it is not just the rise in sea levels, but when coupled with storm surges, rising tides which can cause maximum damage in terms of inundation of low-lying areas. There are areas which are not very high above the sea level, which are at maximum risk,” he said.

Researchers point to the urgent need to prepare the coastal cities for the looming threat, especially considering the important role they play in powering the country’s economy. According to researchers, global economic losses from flooding in 2005 in the world’s largest coastal cities had reached $6 billion, which is estimated to grow to $1 trillion by 2050.

A recent study conducted by researchers from Indian institute of Technology Bombay, ‘Effect of climate change on shoreline shifts at a straight and continuous coast’, throws light on these concerns, while analysing the impacts of climate change on India’s coasts in terms of coastal sediment transport, shoreline erosion and overall coastal vulnerability. The study takes into consideration the coast of Udupi in Karnataka along India’s western coastline which is one of the rapidly changing coastal stretches, and highlights that the effects of climate change could be worse than expected in terms of erosion along the coastline. “In future, higher waves may occur more frequently with corresponding reduction in the frequency of lower waves,” states the research paper.

According to the research, recent analysis of satellite images indicates that the shoreline under consideration is undergoing continuous erosion with an annual average rate of 1.46 m/yr, that the trend of significant erosion noticed in the past will continue in the future as well and that such rate over the next 35 years would go up to 2.21 m/yr. This could be because of the increase in wave forcing in future.

“There are definitely going to be effects on storms due to climate change. We are now focussing on gathering more data and constructing models which can give us accurate projections of estimate sea level rise along the Indian coast. The aim is to prepare maps which can show how much land we will lose. The topography is very important to make that assessment and we are working on that,” added Shenoi.

Scientists are also concerned about the fact that the Indian ocean is warming up faster than other oceans. The increased heat content can fuel stronger storms along the coasts, which could be drastic and more areas can face the risk of inundation. Higher waves could occur more frequently.

Even as sea level rise takes a lot longer to respond to global warming, researchers emphasize that the most evident impact could be expected on the coastlines and countries should take that into consideration during policymaking on climate change to safeguard their coasts.

“Keeping sea level rise to 3-9 meters or roughly 10 to 30 feet over several thousand years is likely too optimistic unless society finds ways to quickly reach zero emissions and lower the CO2 in the atmosphere,” says the research paper published in Nature Climate Change.

“We now know how much more carbon we can emit to keep below a certain temperature. One way to begin looking at it from a policy standpoint is to ask the question, ‘how much sea level rise can we tolerate?’” Clark said.